What Is The Advantage In Animals Coupling Nitrogenous Waste

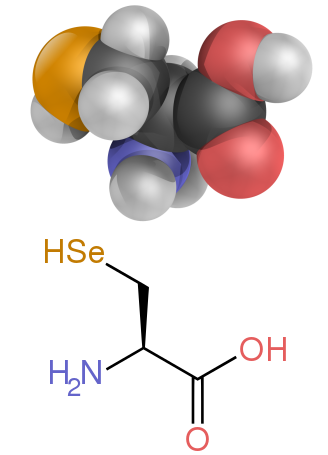

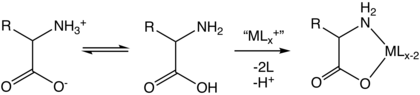

Construction of a generic L-amino acid in the "neutral" class needed for defining a systematic name, without implying that this grade really exists in detectable amounts either in aqueous solution or in the solid land.

Amino acids are organic compounds that incorporate amino[a] (−NH + 3 ) and carboxylic acid (−CO2H) functional groups, along with a side concatenation (R group) specific to each amino acid.[1] The elements present in every amino acrid are carbon (C), hydrogen (H), oxygen (O), and nitrogen (N) (CHON); in improver sulfur (S) is nowadays in the side chains of cysteine and methionine, and selenium (Se) in the less common amino acid selenocysteine. More than 500 naturally occurring amino acids are known to plant monomer units of peptides, including proteins, equally of 2020[update] [2] although only 22 appear in the genetic lawmaking, twenty of which have their own designated codons and 2 of which have special coding mechanisms: Selenocysteine which is nowadays in all eukaryotes and pyrrolysine which is present in some prokaryotes.[iii] [iv]

Amino acids are formally named past the IUPAC-IUBMB Joint Commission on Biochemical Classification[5] in terms of the fictitious "neutral" structure shown in the illustration. For example, the systematic name of alanine is ii-aminopropanoic acid, based on the formula CH3−CH(NHii)−COOH. The Commission justified this arroyo as follows:

The systematic names and formulas given refer to hypothetical forms in which amino groups are unprotonated and carboxyl groups are undissociated. This convention is useful to avert various nomenclatural issues but should not be taken to imply that these structures stand for an appreciable fraction of the amino-acid molecules.

They can be classified according to the locations of the core structural functional groups, as alpha- (α-), beta- (β-), gamma- (γ-) or delta- (δ-) amino acids; other categories relate to polarity, ionization, and side chain group type (aliphatic, acyclic, aromatic, containing hydroxyl or sulfur, etc.). In the form of proteins, amino acid residues form the 2nd-largest component (water being the largest) of human muscles and other tissues.[half-dozen] Beyond their office as residues in proteins, amino acids participate in a number of processes such as neurotransmitter ship and biosynthesis.

History [edit]

The first few amino acids were discovered in the early 1800s.[vii] [eight] In 1806, French chemists Louis-Nicolas Vauquelin and Pierre Jean Robiquet isolated a compound from asparagus that was subsequently named asparagine, the first amino acid to be discovered.[9] [x] Cystine was discovered in 1810,[xi] although its monomer, cysteine, remained undiscovered until 1884.[12] [10] [b] Glycine and leucine were discovered in 1820.[13] The last of the 20 common amino acids to exist discovered was threonine in 1935 by William Cumming Rose, who also determined the essential amino acids and established the minimum daily requirements of all amino acids for optimal growth.[14] [15]

The unity of the chemical category was recognized by Wurtz in 1865, but he gave no item name to it.[16] The first use of the term "amino acid" in the English language dates from 1898,[17] while the German term, Aminosäure , was used earlier.[xviii] Proteins were establish to yield amino acids after enzymatic digestion or acid hydrolysis. In 1902, Emil Fischer and Franz Hofmeister independently proposed that proteins are formed from many amino acids, whereby bonds are formed between the amino group of one amino acid with the carboxyl group of another, resulting in a linear structure that Fischer termed "peptide".[19]

General structure [edit]

In the structure shown at the top of the page R represents a side concatenation specific to each amino acid. The carbon atom adjacent to the carboxyl group is called the α–carbon. Amino acids containing an amino grouping bonded directly to the α-carbon are referred to as α-amino acids.[20] These include proline and hydroxyproline,[c] which are secondary amines. In the past they were often chosen imino acids, a misnomer because they exercise not contain an imine group HN=C.[21] The obsolete term remains frequent.

Isomerism [edit]

The mutual natural forms of amino acids have the structure −NH + 3 (−NH + 2 − in the case of proline) and −CO − 2 functional groups fastened to the same C cantlet, and are thus α-amino acids. With the exception of achiral glycine, natural amino acids have the L configuration,[22] and are the simply ones found in proteins during translation in the ribosome.

The L and D convention for amino acid configuration refers non to the optical activity of the amino acrid itself but rather to the optical activity of the isomer of glyceraldehyde from which that amino acid tin can, in theory, be synthesized (D-glyceraldehyde is dextrorotatory; 50-glyceraldehyde is levorotatory).

An alternative convention is to employ the (Southward) and (R) designators to specify the absolute configuration.[23] Almost all of the amino acids in proteins are (S) at the α carbon, with cysteine being (R) and glycine not-chiral.[24] Cysteine has its side concatenation in the same geometric location as the other amino acids, but the R/S terminology is reversed because sulfur has higher atomic number compared to the carboxyl oxygen which gives the side chain a college priority by the Cahn-Ingold-Prelog sequence rules, whereas the atoms in most other side chains give them lower priority compared to the carboxyl group.[23]

D-amino acid residues are found in some proteins, but they are rare.

Side chains [edit]

Amino acids are designated as α- when the amino nitrogen atom is attached to the α-carbon, the carbon cantlet next to the carboxylate grouping.

In all cases below in this section the values (if whatsoever) refer to the ionization of the groups as amino acid residues in proteins. They are not values for the free amino acids (which are of piddling biochemical importance).

Aliphatic side-chains [edit]

Several side-chains contain simply H and C, and do not ionize. These are equally follows (with iii- and one-letter symbols in parentheses):

- Glycine (Gly, G): H−

- Alanine (Ala, A): CHiii−

- Valine (Val, 5): (CHthree)2CH−

- Leucine (Leu, L): (CHiii)2CHCH2−

- Isoleucine (Ile, I): CHiiiCH2CH(CHiii)

- Proline (Pro, P): −CH2CHtwoCH2− cyclized onto the amine

Polar neutral side-chains [edit]

Two aminoacids contain alcohol side-chains. These practise not ionize in normal conditions, though ane, serine, becomes deprotonated during the catalysis by serine proteases: this is an case of astringent perturbation, and is not characteristic of serine residues in general.

Threonine has two chiral centers, not simply the 50 (2S) chiral middle at the α-carbon shared by all amino acids apart from achiral glycine, but also (iiiR) at the β-carbon. The total stereochemical specification is L-threonine (iiS,3R).

Amide side-chains [edit]

Two amino acids have amide side-chains, as follows:

- Asparagine (Asn, North): NH2COCH2−

- Glutamine (Gln, Q): NH2COCHtwoCH2−

These side-chains do not ionize in the normal range of pH.

Sulfur-containing side-bondage [edit]

Two side-chains contain sulfur atoms, of which ane ionizes in the normal range (with indicated) and the other does not:

Aromatic side-chains [edit]

Side-chains of phenylalanine (left), tyrosine (middle) and tryptophan (correct)

Three amino acids have aromatic ring structures as side-bondage, as illustrated. Of these, tyrosine ionizes in the normal range; the other two practice non).

Anionic side-chains [edit]

2 amino acids take side-chains that are anions at ordinary pH. These amino acids are often referred to as if carboxylic acids only are more correctly called carboxylates, as they are deprotonated at well-nigh relevant pH values. The anionic carboxylate groups deport as Brønsted bases in all circumstances except for enzymes like pepsin that act in environments of very low pH like the mammalian breadbasket.

Cationic side-chains [edit]

Side-chains of histidine (left), lysine (middle) and arginine (correct)

There are 3 amino acids with side-chains that are cations at neutral pH (though in one, histidine, cationic and neutral forms both be). They are unremarkably called basic amino acids, but this term is misleading: histidine tin human activity both as a Brønsted acid and as a Brønsted base at neutral pH, lysine acts as a Brønsted acid, and arginine has a fixed positive charge and does not ionize in neutral atmospheric condition. The names histidinium, lysinium and argininium would be more accurate names for the structures, merely have essentially no currency.

β- and γ-amino acids [edit]

Amino acids with the structure NH + 3 −CXY−CXY−CO − 2 , such every bit β-alanine, a component of carnosine and a few other peptides, are β-amino acids. Ones with the structure NH + 3 −CXY−CXY−CXY−CO − 2 are γ-amino acids, and and then on, where 10 and Y are 2 substituents (i of which is commonly H).[5]

Zwitterions [edit]

Ionization and Brønsted character of N-terminal amino, C-last carboxylate, and side chains of amino acid residues

In aqueous solution amino acids at moderate pH be as zwitterions, i.e. as dipolar ions with both NH + 3 and CO − 2 in charged states, so the overall construction is NH + 3 −CHR−CO − 2 . At physiological pH the so-called "neutral forms" −NH2−CHR−CO2H are not present to any measurable degree.[25] Although the two charges in the real structure add together upward to zilch it is misleading and incorrect to call a species with a internet charge of zero "uncharged".

At very depression pH (below 3), the caboxylate group becomes protonated and the structure becomes an ammonio carboxylic acid, NH + 3 −CHR−CO2H. This is relevant for enzymes like pepsin that are agile in acidic environments such every bit the mammalian stomach and lysosomes, but does not significantly use to intracellular enzymes. At very high pH (greater than ten, not normally seen in physiological weather condition), the ammonio group is deprotonated to requite NH2−CHR−CO − ii .

Although various definitions of acids and bases are used in chemical science, the only one that is useful for chemistry in aqueous solution is that of Brønsted:[26] an acid is a species that can donate a proton to another species, and a base is one that can accept a proton. This criterion is used to label the groups in the above illustration. Notice that aspartate and glutamate are the principal groups that deed every bit Brønsted bases, and the common references to these as acidic amino acids (together with the C terminal) is completely wrong and misleading. Likewise the so-called basic amino acids include one (histidine) that acts as both a Brønsted acrid and a base, one (lysine) that acts primarily as a Brønsted acrid, and one (arginine) that is normally irrelevant to acid-base of operations behavior as information technology has a fixed positive charge. In addition, tyrosine and cysteine, which human activity primarily as acids at neutral pH, are usually forgotten in the usual classification.

Isoelectric point [edit]

Composite of titration curves of twenty proteinogenic amino acids grouped by side chain category

For amino acids with uncharged side-chains the zwitterion predominates at pH values between the 2 pM a values, but coexists in equilibrium with small amounts of cyberspace negative and net positive ions. At the midpoint between the ii p1000 a values, the trace amount of net negative and trace of net positive ions residue, so that average net accuse of all forms present is aught.[27] This pH is known as the isoelectric point pI, and so pI = 1 / ii (pG a1 + pK a2).

For amino acids with charged side bondage, the pK a of the side chain is involved. Thus for aspartate or glutamate with negative side chains, the terminal amino grouping is essentially entirely in the charged grade NH + 3 , but this positive accuse needs to exist balanced by the state with only one C-terminal carboxylate grouping is negatively charged. This occurs halfway between the two carboxylate pChiliad a values: pI = 1 / 2 (pGrand a1 + pK a(R)), where pK a(R) is the side chain pK a.

Similar considerations apply to other amino acids with ionizable side-bondage, including not only glutamate (like to aspartate), but also cysteine, histidine, lysine, tyrosine and arginine with positive side chains

Amino acids have zero mobility in electrophoresis at their isoelectric betoken, although this behaviour is more usually exploited for peptides and proteins than single amino acids. Zwitterions accept minimum solubility at their isoelectric point, and some amino acids (in particular, with nonpolar side chains) tin exist isolated by precipitation from water by adjusting the pH to the required isoelectric betoken.

Physicochemical properties of amino acids [edit]

The ca. twenty approved amino acids tin be classified according to their properties. Of import factors are accuse, hydrophilicity or hydrophobicity, size, and functional groups.[22] These properties influence protein structure and protein–protein interactions. The water-soluble proteins tend to have their hydrophobic residues (Leu, Ile, Val, Phe, and Trp) buried in the middle of the protein, whereas hydrophilic side chains are exposed to the aqueous solvent. (Notation that in biochemistry, a balance refers to a specific monomer within the polymeric chain of a polysaccharide, protein or nucleic acid.) The integral membrane proteins tend to have outer rings of exposed hydrophobic amino acids that ballast them into the lipid bilayer. Some peripheral membrane proteins have a patch of hydrophobic amino acids on their surface that locks onto the membrane. In similar fashion, proteins that accept to demark to positively charged molecules have surfaces rich with negatively charged amino acids like glutamate and aspartate, while proteins binding to negatively charged molecules accept surfaces rich with positively charged chains like lysine and arginine. For instance, lysine and arginine are highly enriched in low-complexity regions of nucleic-acid binding proteins.[28] At that place are various hydrophobicity scales of amino acid residues.[29]

Some amino acids take special properties such as cysteine, that tin course covalent disulfide bonds to other cysteine residues, proline that forms a bicycle to the polypeptide backbone, and glycine that is more flexible than other amino acids.

Furthermore, glycine and proline are highly enriched within low complexity regions of eukaryotic and prokaryotic proteins, whereas the contrary (under-represented) has been observed for highly reactive, or complex, or hydrophobic amino acids, such as cysteine, phenylalanine, tryptophan, methionine, valine, leucine, isoleucine.[28] [30] [31]

Many proteins undergo a range of posttranslational modifications, whereby additional chemic groups are attached to the amino acid side chains. Some modifications can produce hydrophobic lipoproteins,[32] or hydrophilic glycoproteins.[33] These type of modification allow the reversible targeting of a protein to a membrane. For example, the improver and removal of the fatty acid palmitic acid to cysteine residues in some signaling proteins causes the proteins to adhere and then detach from cell membranes.[34]

Tabular array of standard amino acid abbreviations and backdrop [edit]

Although one-letter symbols are included in the tabular array, IUPAC–IUBMB recommend[v] that "Use of the one-alphabetic character symbols should be restricted to the comparison of long sequences".

| Amino acid | 3- and 1-letter symbols | Side concatenation | Hydropathy index[35] | Tooth absorptivity[36] | Molecular mass | Affluence in proteins (%)[37] | Standard genetic coding, IUPAC notation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 1 | Form | Polarity[38] | Net charge at pH 7.4[38] | Wavelength, λ max (nm) | Coefficient ε (mM−1·cm−1) | |||||

| Alanine | Ala | A | Aliphatic | Nonpolar | Neutral | one.8 | 89.094 | viii.76 | GCN | ||

| Arginine | Arg | R | Fixed cation | Basic polar | Positive | −4.5 | 174.203 | 5.78 | MGR, CGY[39] | ||

| Asparagine | Asn | N | Amide | Polar | Neutral | −3.5 | 132.119 | three.93 | AAY | ||

| Aspartate | Asp | D | Anion | Brønsted base | Negative | −iii.5 | 133.104 | v.49 | GAY | ||

| Cysteine | Cys | C | Thiol | Brønsted acid | Neutral | 2.v | 250 | 0.iii | 121.154 | i.38 | UGY |

| Glutamine | Gln | Q | Amide | Polar | Neutral | −3.5 | 146.146 | 3.nine | CAR | ||

| Glutamate | Glu | East | Anion | Brønsted base | Negative | −3.5 | 147.131 | six.32 | GAR | ||

| Glycine | Gly | G | Aliphatic | Nonpolar | Neutral | −0.4 | 75.067 | seven.03 | GGN | ||

| Histidine | His | H | Aromatic cation | Brønsted acid and base | Positive, 10% Neutral, 90% | −three.ii | 211 | 5.9 | 155.156 | 2.26 | CAY |

| Isoleucine | Ile | I | Aliphatic | Nonpolar | Neutral | 4.v | 131.175 | 5.49 | AUH | ||

| Leucine | Leu | Fifty | Aliphatic | Nonpolar | Neutral | iii.viii | 131.175 | ix.68 | YUR, CUY[40] | ||

| Lysine | Lys | Grand | Cation | Brønsted acid | Positive | −three.ix | 146.189 | five.xix | AAR | ||

| Methionine | Met | One thousand | Thioether | Nonpolar | Neutral | i.9 | 149.208 | 2.32 | AUG | ||

| Phenylalanine | Phe | F | Aromatic | Nonpolar | Neutral | ii.8 | 257, 206, 188 | 0.two, nine.3, 60.0 | 165.192 | 3.87 | UUY |

| Proline | Pro | P | Circadian | Nonpolar | Neutral | −one.vi | 115.132 | 5.02 | CCN | ||

| Serine | Ser | S | Hydroxylic | Polar | Neutral | −0.8 | 105.093 | seven.14 | UCN, AGY | ||

| Threonine | Thr | T | Hydroxylic | Polar | Neutral | −0.7 | 119.119 | five.53 | ACN | ||

| Tryptophan | Trp | W | Aromatic | Nonpolar | Neutral | −0.9 | 280, 219 | 5.half-dozen, 47.0 | 204.228 | 1.25 | UGG |

| Tyrosine | Tyr | Y | Aromatic | Brønsted acrid | Neutral | −1.three | 274, 222, 193 | 1.4, eight.0, 48.0 | 181.191 | ii.91 | UAY |

| Valine | Val | 5 | Aliphatic | Nonpolar | Neutral | four.2 | 117.148 | vi.73 | GUN | ||

Two boosted amino acids are in some species coded for by codons that are unremarkably interpreted as stop codons:

| 21st and 22nd amino acids | 3-letter | ane-letter | Molecular mass |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selenocysteine | Sec | U | 168.064 |

| Pyrrolysine | Pyl | O | 255.313 |

In addition to the specific amino acid codes, placeholders are used in cases where chemic or crystallographic analysis of a peptide or protein cannot conclusively determine the identity of a residue. They are also used to summarise conserved protein sequence motifs. The use of single letters to indicate sets of similar residues is like to the use of abridgement codes for degenerate bases.[41] [42]

| Ambiguous amino acids | 3-letter | 1-alphabetic character | Amino acids included | Codons included |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any / unknown | Xaa | Ten | All | NNN |

| Asparagine or aspartate | Asx | B | D, N | RAY |

| Glutamine or glutamate | Glx | Z | E, Q | SAR |

| Leucine or isoleucine | Xle | J | I, L | YTR, ATH, CTY[43] |

| Hydrophobic | Φ | Five, I, 50, F, W, Y, 1000 | NTN, TAY, TGG | |

| Aromatic | Ω | F, W, Y, H | YWY, TTY, TGG[44] | |

| Aliphatic (non-effluvious) | Ψ | 5, I, L, M | VTN, TTR[45] | |

| Small | π | P, G, A, Southward | BCN, RGY, GGR | |

| Hydrophilic | ζ | S, T, H, N, Q, Eastward, D, K, R | VAN, WCN, CGN, AGY[46] | |

| Positively-charged | + | K, R, H | ARR, Weep, CGR | |

| Negatively-charged | − | D, E | GAN |

Unk is sometimes used instead of Xaa, but is less standard.

Ter or * (from termination) is used in annotation for mutations in proteins when a stop codon occurs. It correspond to no amino acid at all.[47]

In improver, many nonstandard amino acids have a specific lawmaking. For example, several peptide drugs, such every bit Bortezomib and MG132, are artificially synthesized and retain their protecting groups, which have specific codes. Bortezomib is Pyz–Phe–boroLeu, and MG132 is Z–Leu–Leu–Leu–al. To aid in the analysis of protein structure, photo-reactive amino acrid analogs are bachelor. These include photoleucine (pLeu) and photomethionine (pMet).[48]

Occurrence and functions in biochemistry [edit]

β-Alanine and its α-alanine isomer

Amino acids which have the amine group attached to the (blastoff-) carbon cantlet next to the carboxyl group have chief importance in living organisms since they participate in protein synthesis.[49] They are known as 2-, blastoff-, or α-amino acids (generic formula HtwoNCHRCOOH in virtually cases,[d] where R is an organic substituent known every bit a "side concatenation");[50] often the term "amino acid" is used to refer specifically to these. They include the 22 proteinogenic ("protein-building") amino acids,[51] [52] [53] which combine into peptide chains ("polypeptides") to form the building blocks of a vast array of proteins.[49] These are all L-stereoisomers ("left-handed" enantiomers), although a few D-amino acids ("right-handed") occur in bacterial envelopes, every bit a neuromodulator (D-serine), and in some antibiotics.[54]

Many proteinogenic and non-proteinogenic amino acids accept biological functions. For example, in the human brain, glutamate (standard glutamic acrid) and gamma-aminobutyric acrid ("GABA", nonstandard gamma-amino acid) are, respectively, the chief excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters.[55] Hydroxyproline, a major component of the connective tissue collagen, is synthesised from proline. Glycine is a biosynthetic precursor to porphyrins used in red claret cells. Carnitine is used in lipid transport. Nine proteinogenic amino acids are called "essential" for humans because they cannot be produced from other compounds by the man body and then must be taken in as nutrient. Others may be conditionally essential for certain ages or medical conditions. Essential amino acids may also vary from species to species.[e] Because of their biological significance, amino acids are of import in nutrition and are unremarkably used in nutritional supplements, fertilizers, feed, and nutrient technology. Industrial uses include the production of drugs, biodegradable plastics, and chiral catalysts.

Proteinogenic amino acids [edit]

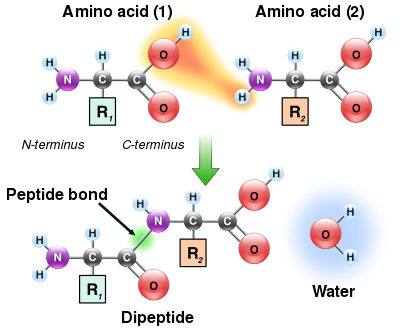

Amino acids are the precursors to proteins. They join by condensation reactions to form short polymer bondage chosen peptides or longer chains called either polypeptides or proteins. These chains are linear and unbranched, with each amino acid residual within the chain fastened to ii neighboring amino acids. In Nature, the process of making proteins encoded by Deoxyribonucleic acid/RNA genetic material is called translation and involves the pace-past-footstep improver of amino acids to a growing protein chain by a ribozyme that is called a ribosome.[56] The lodge in which the amino acids are added is read through the genetic lawmaking from an mRNA template, which is an RNA copy of ane of the organism's genes.

Xx-2 amino acids are naturally incorporated into polypeptides and are called proteinogenic or natural amino acids.[22] Of these, 20 are encoded by the universal genetic lawmaking. The remaining 2, selenocysteine and pyrrolysine, are incorporated into proteins past unique synthetic mechanisms. Selenocysteine is incorporated when the mRNA being translated includes a SECIS element, which causes the UGA codon to encode selenocysteine instead of a stop codon.[57] Pyrrolysine is used by some methanogenic archaea in enzymes that they use to produce methane. Information technology is coded for with the codon UAG, which is ordinarily a cease codon in other organisms.[58] This UAG codon is followed by a PYLIS downstream sequence.[59]

Several independent evolutionary studies have suggested that Gly, Ala, Asp, Val, Ser, Pro, Glu, Leu, Thr may belong to a group of amino acids that constituted the early genetic code, whereas Cys, Met, Tyr, Trp, His, Phe may vest to a group of amino acids that constituted later additions of the genetic code.[60] [61] [62]

Standard vs nonstandard amino acids [edit]

The twenty amino acids that are encoded directly by the codons of the universal genetic lawmaking are called standard or canonical amino acids. A modified form of methionine (N-formylmethionine) is oft incorporated in place of methionine equally the initial amino acid of proteins in bacteria, mitochondria and chloroplasts. Other amino acids are called nonstandard or non-canonical. Most of the nonstandard amino acids are also non-proteinogenic (i.e. they cannot be incorporated into proteins during translation), but ii of them are proteinogenic, as they can be incorporated translationally into proteins by exploiting information not encoded in the universal genetic code.

The ii nonstandard proteinogenic amino acids are selenocysteine (present in many non-eukaryotes equally well every bit most eukaryotes, but not coded directly by Deoxyribonucleic acid) and pyrrolysine (found but in some archaea and at least one bacterium). The incorporation of these nonstandard amino acids is rare. For example, 25 man proteins include selenocysteine in their main construction,[63] and the structurally characterized enzymes (selenoenzymes) employ selenocysteine as the catalytic moiety in their agile sites.[64] Pyrrolysine and selenocysteine are encoded via variant codons. For example, selenocysteine is encoded by cease codon and SECIS element.[65] [66] [67]

Due north-formylmethionine (which is often the initial amino acid of proteins in bacteria, mitochondria, and chloroplasts) is more often than not considered equally a form of methionine rather than every bit a separate proteinogenic amino acrid. Codon–tRNA combinations not found in nature tin can likewise be used to "aggrandize" the genetic code and form novel proteins known as alloproteins incorporating non-proteinogenic amino acids.[68] [69] [70]

Non-proteinogenic amino acids [edit]

Aside from the 22 proteinogenic amino acids, many not-proteinogenic amino acids are known. Those either are not found in proteins (for example carnitine, GABA, levothyroxine) or are non produced directly and in isolation by standard cellular machinery (for example, hydroxyproline and selenomethionine).

Non-proteinogenic amino acids that are found in proteins are formed by post-translational modification, which is modification after translation during protein synthesis. These modifications are often essential for the function or regulation of a protein. For example, the carboxylation of glutamate allows for better binding of calcium cations,[71] and collagen contains hydroxyproline, generated by hydroxylation of proline.[72] Another example is the formation of hypusine in the translation initiation cistron EIF5A, through modification of a lysine rest.[73] Such modifications tin can also determine the localization of the protein, due east.g., the addition of long hydrophobic groups tin cause a protein to bind to a phospholipid membrane.[74]

Some non-proteinogenic amino acids are not plant in proteins. Examples include 2-aminoisobutyric acid and the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid. Non-proteinogenic amino acids often occur equally intermediates in the metabolic pathways for standard amino acids – for example, ornithine and citrulline occur in the urea bike, part of amino acrid catabolism (come across below).[75] A rare exception to the dominance of α-amino acids in biology is the β-amino acid beta alanine (3-aminopropanoic acrid), which is used in plants and microorganisms in the synthesis of pantothenic acid (vitamin B5), a component of coenzyme A.[76]

In homo nutrition [edit]

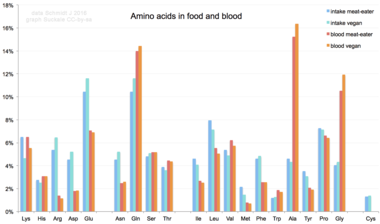

Share of amino acid in diverse human diets and the resulting mix of amino acids in human blood serum. Glutamate and glutamine are the most frequent in nutrient at over ten%, while alanine, glutamine, and glycine are the most common in claret.

When taken upwardly into the human body from the diet, the twenty standard amino acids either are used to synthesize proteins, other biomolecules, or are oxidized to urea and carbon dioxide as a source of free energy.[77] The oxidation pathway starts with the removal of the amino group by a transaminase; the amino group is then fed into the urea bike. The other production of transamidation is a keto acid that enters the citric acid bike.[78] Glucogenic amino acids can also be converted into glucose, through gluconeogenesis.[79] Of the 20 standard amino acids, nine (His, Ile, Leu, Lys, Met, Phe, Thr, Trp and Val) are chosen essential amino acids because the human body cannot synthesize them from other compounds at the level needed for normal growth, so they must be obtained from food.[eighty] [81] [82] In addition, cysteine, tyrosine, and arginine are considered semiessential amino acids, and taurine a semiessential aminosulfonic acid in children. The metabolic pathways that synthesize these monomers are not fully adult.[83] [84] The amounts required also depend on the age and wellness of the individual, so information technology is hard to brand full general statements about the dietary requirement for some amino acids. Dietary exposure to the nonstandard amino acid BMAA has been linked to homo neurodegenerative diseases, including ALS.[85] [86]

Resistance training stimulates muscle protein synthesis (MPS) for a catamenia of up to 48 hours following exercise (shown by lighter dotted line).[89] Ingestion of a poly peptide-rich meal at any point during this period volition augment the exercise-induced increase in muscle protein synthesis (shown by solid lines).[89]

Not-protein functions [edit]

In humans, non-protein amino acids too have important roles as metabolic intermediates, such as in the biosynthesis of the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA). Many amino acids are used to synthesize other molecules, for instance:

- Tryptophan is a precursor of the neurotransmitter serotonin.[93]

- Tyrosine (and its precursor phenylalanine) are precursors of the catecholamine neurotransmitters dopamine, epinephrine and norepinephrine and various trace amines.

- Phenylalanine is a precursor of phenethylamine and tyrosine in humans. In plants, it is a precursor of various phenylpropanoids, which are important in institute metabolism.

- Glycine is a precursor of porphyrins such as heme.[94]

- Arginine is a precursor of nitric oxide.[95]

- Ornithine and Due south-adenosylmethionine are precursors of polyamines.[96]

- Aspartate, glycine, and glutamine are precursors of nucleotides.[97] However, non all of the functions of other abundant nonstandard amino acids are known.

Some nonstandard amino acids are used as defenses against herbivores in plants.[98] For instance, canavanine is an counterpart of arginine that is plant in many legumes,[99] and in particularly big amounts in Canavalia gladiata (sword bean).[100] This amino acrid protects the plants from predators such as insects and tin can crusade illness in people if some types of legumes are eaten without processing.[101] The non-poly peptide amino acid mimosine is institute in other species of legume, in particular Leucaena leucocephala.[102] This compound is an analogue of tyrosine and tin poison animals that graze on these plants.

Uses in industry [edit]

Amino acids are used for a diversity of applications in industry, only their main use is every bit additives to animal feed. This is necessary, since many of the bulk components of these feeds, such equally soybeans, either have low levels or lack some of the essential amino acids: lysine, methionine, threonine, and tryptophan are well-nigh important in the product of these feeds.[103] In this industry, amino acids are also used to chelate metal cations in gild to ameliorate the absorption of minerals from supplements, which may be required to improve the health or productivity of these animals.[104]

The food manufacture is also a major consumer of amino acids, in particular, glutamic acid, which is used as a flavor enhancer,[105] and aspartame (aspartylphenylalanine one-methyl ester) equally a low-calorie bogus sweetener.[106] Like applied science to that used for fauna nutrition is employed in the human nutrition industry to alleviate symptoms of mineral deficiencies, such as anemia, by improving mineral absorption and reducing negative side effects from inorganic mineral supplementation.[107]

The chelating ability of amino acids has been used in fertilizers for agriculture to facilitate the delivery of minerals to plants in social club to correct mineral deficiencies, such as fe chlorosis. These fertilizers are besides used to prevent deficiencies from occurring and to improve the overall health of the plants.[108] The remaining production of amino acids is used in the synthesis of drugs and cosmetics.[103]

Similarly, some amino acids derivatives are used in pharmaceutical industry. They include 5-HTP (5-hydroxytryptophan) used for experimental handling of depression,[109] L-DOPA (L-dihydroxyphenylalanine) for Parkinson's treatment,[110] and eflornithine drug that inhibits ornithine decarboxylase and used in the treatment of sleeping sickness.[111]

Expanded genetic lawmaking [edit]

Since 2001, 40 non-natural amino acids take been added into protein by creating a unique codon (recoding) and a respective transfer-RNA:aminoacyl – tRNA-synthetase pair to encode it with various physicochemical and biological backdrop in club to be used as a tool to exploring protein construction and function or to create novel or enhanced proteins.[68] [69]

Nullomers [edit]

Nullomers are codons that in theory code for an amino acrid, however, in nature there is a selective bias against using this codon in favor of another, for example bacteria prefer to apply CGA instead of AGA to code for arginine.[112] This creates some sequences that do not appear in the genome. This feature tin can be taken reward of and used to create new selective cancer-fighting drugs[113] and to forestall cross-contamination of Deoxyribonucleic acid samples from law-breaking-scene investigations.[114]

Chemical building blocks [edit]

Amino acids are of import every bit low-cost feedstocks. These compounds are used in chiral pool synthesis as enantiomerically pure edifice blocks.[115]

Amino acids accept been investigated equally precursors chiral catalysts, such every bit for asymmetric hydrogenation reactions, although no commercial applications exist.[116]

Biodegradable plastics [edit]

Amino acids take been considered as components of biodegradable polymers, which have applications as environmentally friendly packaging and in medicine in drug delivery and the construction of prosthetic implants.[117] An interesting example of such materials is polyaspartate, a water-soluble biodegradable polymer that may have applications in disposable diapers and agriculture.[118] Due to its solubility and power to chelate metal ions, polyaspartate is also being used as a biodegradable antiscaling agent and a corrosion inhibitor.[119] [120] In addition, the aromatic amino acrid tyrosine has been considered as a possible replacement for phenols such as bisphenol A in the manufacture of polycarbonates.[121]

Synthesis [edit]

The Strecker amino acid synthesis

Chemical synthesis [edit]

The commercial product of amino acids normally relies on mutant bacteria that overproduce individual amino acids using glucose every bit a carbon source. Some amino acids are produced past enzymatic conversions of synthetic intermediates. ii-Aminothiazoline-4-carboxylic acid is an intermediate in one industrial synthesis of 50-cysteine for example. Aspartic acid is produced past the add-on of ammonia to fumarate using a lyase.[122]

Biosynthesis [edit]

In plants, nitrogen is first assimilated into organic compounds in the grade of glutamate, formed from blastoff-ketoglutarate and ammonia in the mitochondrion. For other amino acids, plants use transaminases to move the amino group from glutamate to some other alpha-keto acrid. For example, aspartate aminotransferase converts glutamate and oxaloacetate to blastoff-ketoglutarate and aspartate.[123] Other organisms employ transaminases for amino acid synthesis, too.

Nonstandard amino acids are usually formed through modifications to standard amino acids. For example, homocysteine is formed through the transsulfuration pathway or by the demethylation of methionine via the intermediate metabolite Southward-adenosylmethionine,[124] while hydroxyproline is made by a post translational modification of proline.[125]

Microorganisms and plants synthesize many uncommon amino acids. For example, some microbes brand two-aminoisobutyric acid and lanthionine, which is a sulfide-bridged derivative of alanine. Both of these amino acids are found in peptidic lantibiotics such equally alamethicin.[126] All the same, in plants, 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acrid is a small disubstituted cyclic amino acid that is an intermediate in the production of the plant hormone ethylene.[127]

Reactions [edit]

Amino acids undergo the reactions expected of the constituent functional groups.[128] [129]

Peptide bond germination [edit]

The condensation of ii amino acids to form a dipeptide. The two amino acrid residues are linked through a peptide bail

As both the amine and carboxylic acid groups of amino acids can react to form amide bonds, 1 amino acid molecule tin react with another and get joined through an amide linkage. This polymerization of amino acids is what creates proteins. This condensation reaction yields the newly formed peptide bond and a molecule of h2o. In cells, this reaction does not occur direct; instead, the amino acid is offset activated by attachment to a transfer RNA molecule through an ester bond. This aminoacyl-tRNA is produced in an ATP-dependent reaction carried out by an aminoacyl tRNA synthetase.[130] This aminoacyl-tRNA is and so a substrate for the ribosome, which catalyzes the attack of the amino group of the elongating protein concatenation on the ester bond.[131] As a effect of this machinery, all proteins fabricated by ribosomes are synthesized starting at their Northward-terminus and moving toward their C-terminus.

Nevertheless, not all peptide bonds are formed in this way. In a few cases, peptides are synthesized past specific enzymes. For case, the tripeptide glutathione is an essential role of the defenses of cells confronting oxidative stress. This peptide is synthesized in two steps from free amino acids.[132] In the first step, gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase condenses cysteine and glutamate through a peptide bond formed betwixt the side chain carboxyl of the glutamate (the gamma carbon of this side concatenation) and the amino group of the cysteine. This dipeptide is so condensed with glycine past glutathione synthetase to class glutathione.[133]

In chemistry, peptides are synthesized by a variety of reactions. 1 of the nigh-used in solid-stage peptide synthesis uses the aromatic oxime derivatives of amino acids as activated units. These are added in sequence onto the growing peptide chain, which is attached to a solid resin support.[134] Libraries of peptides are used in drug discovery through loftier-throughput screening.[135]

The combination of functional groups permit amino acids to be effective polydentate ligands for metallic–amino acid chelates.[136] The multiple side chains of amino acids can too undergo chemical reactions.

Catabolism [edit]

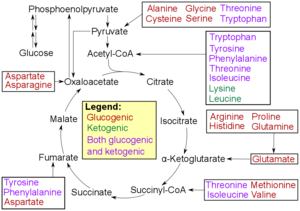

Catabolism of proteinogenic amino acids. Amino acids tin can be classified co-ordinate to the properties of their main degradation products:[137]

* Glucogenic, with the products having the power to form glucose by gluconeogenesis

* Ketogenic, with the products non having the ability to form glucose. These products may still be used for ketogenesis or lipid synthesis.

* Amino acids catabolized into both glucogenic and ketogenic products.

Deposition of an amino acid often involves deamination by moving its amino grouping to alpha-ketoglutarate, forming glutamate. This process involves transaminases, often the aforementioned every bit those used in amination during synthesis. In many vertebrates, the amino grouping is and then removed through the urea wheel and is excreted in the grade of urea. However, amino acrid degradation can produce uric acrid or ammonia instead. For case, serine dehydratase converts serine to pyruvate and ammonia.[97] After removal of ane or more than amino groups, the remainder of the molecule tin can sometimes exist used to synthesize new amino acids, or it can be used for energy by entering glycolysis or the citric acid cycle, as detailed in epitome at right.

Complexation [edit]

Amino acids are bidentate ligands, forming transition metal amino acrid complexes.[138]

Chemical analysis [edit]

The total nitrogen content of organic matter is mainly formed past the amino groups in proteins. The Total Kjeldahl Nitrogen (TKN) is a measure of nitrogen widely used in the analysis of (waste material) water, soil, food, feed and organic thing in general. Every bit the proper noun suggests, the Kjeldahl method is practical. More sensitive methods are available.[139] [140]

Meet besides [edit]

- Amino acid dating

- Beta-peptide

- Degron

- Erepsin

- Homochirality

- Hyperaminoacidemia

- Leucines

- Miller–Urey experiment

- Nucleic acrid sequence

- RNA codon table

Notes [edit]

- ^ Strictly ammonio, every bit amino refers to uncharged −NH2 , but this term is almost never used.

- ^ The tardily discovery is explained past the fact that cysteine becomes oxidized to cystine in air.

- ^ Hydroxyproline is present in very few proteins, virtually notably collagen.

- ^ Proline is an exception to this general formula. It lacks the NHii group because of the cyclization of the side chain and is known every bit an imino acrid; it falls under the category of special structured amino acids.

- ^ For example, ruminants such as cows obtain a number of amino acids via microbes in the first two breadbasket chambers.

References [edit]

- ^ Nelson DL, Cox MM (2005). Principles of Biochemistry (4th ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman. ISBN0-7167-4339-6.

- ^ Flissi, Areski; Ricart, Emma; Campart, Clémentine; Chevalier, Mickael; Dufresne, Yoann; Michalik, Juraj; Jacques, Philippe; Flahaut, Christophe; Lisacek, Frédérique; Leclère, Valérie; Pupin, Maude (2020). "Norine: update of the nonribosomal peptide resource". Nucleic Acids Inquiry. 48 (D1): D465–D469. doi:ten.1093/nar/gkz1000. PMC7145658. PMID 31691799.

- ^ Richard Cammack, ed. (2009). "Newsletter 2009". Biochemical Nomenclature Committee of IUPAC and NC-IUBMB. Pyrrolysine. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 16 Apr 2012.

- ^ Rother, Michael; Krzycki, Joseph A. (ane Jan 2010). "Selenocysteine, Pyrrolysine, and the Unique Energy Metabolism of Methanogenic Archaea". Archaea. 2010: 1–14. doi:10.1155/2010/453642. ISSN 1472-3646. PMC2933860. PMID 20847933.

- ^ a b c "Classification and Symbolism for Amino Acids and Peptides". IUPAC-IUB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature. 1983. Archived from the original on 9 October 2008. Retrieved 17 November 2008.

- ^ Latham MC (1997). "Chapter eight. Body limerick, the functions of nutrient, metabolism and energy". Human nutrition in the developing earth. Food and Diet Series – No. 29. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the Un. Archived from the original on viii October 2012. Retrieved ix September 2012.

- ^ Vickery HB, Schmidt CL (1931). "The history of the discovery of the amino acids". Chem. Rev. ix (two): 169–318. doi:ten.1021/cr60033a001.

- ^ Hansen S (May 2015). "Die Entdeckung der proteinogenen Aminosäuren von 1805 in Paris bis 1935 in Illinois" (PDF) (in German). Berlin. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 Dec 2017.

- ^ Vauquelin LN, Robiquet PJ (1806). "The discovery of a new institute principle in Asparagus sativus". Annales de Chimie. 57: 88–93.

- ^ a b Anfinsen CB, Edsall JT, Richards FM (1972). Advances in Protein Chemical science. New York: Academic Press. pp. 99, 103. ISBN978-0-12-034226-6.

- ^ Wollaston WH (1810). "On cystic oxide, a new species of urinary calculus". Philosophical Transactions of the Regal Society. 100: 223–230. doi:10.1098/rstl.1810.0015. S2CID 110151163.

- ^ Baumann E (1884). "Über cystin und cystein". Z Physiol Chem. 8 (iv): 299–305. Archived from the original on 14 March 2011. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Braconnot HM (1820). "Sur la conversion des matières animales en nouvelles substances par le moyen de l'acide sulfurique". Annales de Chimie et de Physique. 2nd Series. 13: 113–125.

- ^ Simoni RD, Colina RL, Vaughan M (September 2002). "The discovery of the amino acrid threonine: the piece of work of William C. Rose [classical article]". The Journal of Biological Chemical science. 277 (37): E25. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(20)74369-3. PMID 12218068. Archived from the original on 10 June 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ McCoy RH, Meyer CE, Rose WC (1935). "Feeding Experiments with Mixtures of Highly Purified Amino Acids. 8. Isolation and Identification of a New Essential Amino Acid". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 112: 283–302. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)74986-7.

- ^ Menten, P. Dictionnaire de chimie: Une approche étymologique et historique. De Boeck, Bruxelles. link Archived 28 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Harper D. "amino-". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2 December 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2010.

- ^ Paal C (1894). "Ueber die Einwirkung von Phenyl‐i‐cyanat auf organische Aminosäuren". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 27: 974–979. doi:10.1002/cber.189402701205. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020.

- ^ Fruton JS (1990). "Affiliate 5- Emil Fischer and Franz Hofmeister". Contrasts in Scientific Style: Research Groups in the Chemic and Biochemical Sciences. Vol. 191. American Philosophical Society. pp. 163–165. ISBN978-0-87169-191-0.

- ^ "Alpha amino acid". The Merriam-Webster.com Medical Dictionary. Merriam-Webster Inc. Archived from the original on 3 January 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2015. .

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2d ed. (the "Aureate Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "Imino acids". doi:10.1351/goldbook.I02959Retrieved 2 Apr 2012

- ^ a b c Creighton Thursday (1993). "Chapter ane". Proteins: structures and molecular backdrop. San Francisco: West. H. Freeman. ISBN978-0-7167-7030-5.

- ^ a b Cahn, R.Due south.; Ingold, C.K.; Prelog, V. (1966). "Specification of Molecular Chirality". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 5 (four): 385–415. doi:x.1002/anie.196603851.

- ^ Hatem SM (2006). "Gas chromatographic determination of Amino Acid Enantiomers in tobacco and bottled wines". University of Giessen. Archived from the original on 22 January 2009. Retrieved 17 Nov 2008.

- ^ Steinhardt, J.; Reynolds, J. A. (1969). Multiple equilibria in proteins. New York: Academic Printing. pp. 176–21. ISBN978-0126654509.

- ^ Brønsted, J. N. (1923). "Einige Bemerkungen über den Begriff der Säuren und Basen" [Remarks on the concept of acids and bases]. Recueil des Travaux Chimiques des Pays-Bas. 42 (eight): 718–728. doi:ten.1002/recl.19230420815.

- ^ Fennema OR (xix June 1996). Food Chemical science tertiary Ed. CRC Printing. pp. 327–328. ISBN978-0-8247-9691-4.

- ^ a b Ntountoumi C, Vlastaridis P, Mossialos D, Stathopoulos C, Iliopoulos I, Promponas V, et al. (Nov 2019). "Depression complexity regions in the proteins of prokaryotes perform of import functional roles and are highly conserved". Nucleic Acids Inquiry. 47 (nineteen): 9998–10009. doi:10.1093/nar/gkz730. PMC6821194. PMID 31504783.

- ^ Urry DW (2004). "The change in Gibbs complimentary free energy for hydrophobic association: Derivation and evaluation by means of inverse temperature transitions". Chemical Physics Letters. 399 (i–3): 177–183. Bibcode:2004CPL...399..177U. doi:10.1016/S0009-2614(04)01565-nine.

- ^ Marcotte EM, Pellegrini M, Yeates TO, Eisenberg D (Oct 1999). "A census of protein repeats". Journal of Molecular Biological science. 293 (1): 151–60. doi:ten.1006/jmbi.1999.3136. PMID 10512723.

- ^ Haerty West, Golding GB (October 2010). Bonen L (ed.). "Low-complexity sequences and unmarried amino acrid repeats: not just "junk" peptide sequences". Genome. 53 (x): 753–62. doi:x.1139/G10-063. PMID 20962881.

- ^ Magee T, Seabra MC (Apr 2005). "Fatty acylation and prenylation of proteins: what'southward hot in fat". Electric current Opinion in Jail cell Biology. 17 (2): 190–196. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2005.02.003. PMID 15780596.

- ^ Pilobello KT, Mahal LK (June 2007). "Deciphering the glycocode: the complexity and analytical challenge of glycomics". Current Opinion in Chemical Biological science. 11 (3): 300–305. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.05.002. PMID 17500024.

- ^ Smotrys JE, Linder ME (2004). "Palmitoylation of intracellular signaling proteins: regulation and office". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 73 (1): 559–587. doi:ten.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073954. PMID 15189153.

- ^ Kyte J, Doolittle RF (May 1982). "A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein". Journal of Molecular Biological science. 157 (1): 105–132. CiteSeerX10.ane.1.458.454. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. PMID 7108955.

- ^ Freifelder D (1983). Physical Biochemistry (2nd ed.). W. H. Freeman and Visitor. ISBN978-0-7167-1315-9. [ page needed ]

- ^ Kozlowski LP (Jan 2017). "Proteome-pI: proteome isoelectric point database". Nucleic Acids Research. 45 (D1): D1112–D1116. doi:10.1093/nar/gkw978. PMC5210655. PMID 27789699.

- ^ a b Hausman RE, Cooper GM (2004). The cell: a molecular approach. Washington, D.C: ASM Press. p. 51. ISBN978-0-87893-214-half-dozen.

- ^ Codons tin also be expressed by: CGN, AGR

- ^ codons can besides be expressed by: CUN, UUR

- ^ Aasland R, Abrams C, Ampe C, Brawl LJ, Bedford MT, Cesareni G, Gimona K, Hurley JH, Jarchau T, Lehto VP, Lemmon MA, Linding R, Mayer BJ, Nagai M, Sudol Thou, Walter U, Winder SJ (February 2002). "Normalization of nomenclature for peptide motifs equally ligands of modular protein domains". FEBS Letters. 513 (i): 141–144. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1968.tb00350.x. PMID 11911894.

- ^ IUPAC–IUB Commission on Biochemical Classification (1972). "A one-letter notation for amino acid sequences". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 31 (four): 641–645. doi:10.1351/pac197231040639. PMID 5080161.

- ^ Codons can also be expressed by: CTN, ATH, TTR; MTY, YTR, ATA; MTY, HTA, YTG

- ^ Codons can also exist expressed past: TWY, CAY, TGG

- ^ Codons can likewise be expressed by: NTR, VTY

- ^ Codons can also be expressed by: VAN, WCN, MGY, CGP

- ^ "HGVS: Sequence Variant Nomenclature, Protein Recommendations". Archived from the original on 24 September 2021. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ Suchanek M, Radzikowska A, Thiele C (April 2005). "Photograph-leucine and photo-methionine let identification of poly peptide–protein interactions in living cells". Nature Methods. 2 (iv): 261–267. doi:10.1038/nmeth752. PMID 15782218.

- ^ a b "Chapter 1: Proteins are the Body'due south Worker Molecules". The Structures of Life. National Institute of Full general Medical Sciences. 27 October 2011. Archived from the original on 7 June 2014. Retrieved xx May 2008.

- ^ Clark, Jim (Baronial 2007). "An introduction to amino acids". chemguide. Archived from the original on 30 April 2015. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ Jakubke H, Sewald N (2008). "Amino acids". Peptides from A to Z: A Concise Encyclopedia. Frg: Wiley-VCH. p. 20. ISBN9783527621170. Archived from the original on 17 May 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ Pollegioni L, Servi S, eds. (2012). Unnatural Amino Acids: Methods and Protocols. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 794. Humana Printing. p. v. doi:x.1007/978-i-61779-331-8. ISBN978-one-61779-331-8. OCLC 756512314. S2CID 3705304.

- ^ Hertweck C (Oct 2011). "Biosynthesis and Charging of Pyrrolysine, the 22nd Genetically Encoded Amino Acid". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 50 (41): 9540–9541. doi:10.1002/anie.201103769. PMID 21796749. S2CID 5359077.

- ^ Michal G, Schomburg D, eds. (2012). Biochemical Pathways: An Atlas of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (2nd ed.). Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 5. ISBN978-0-470-14684-2.

- ^ Petroff OA (December 2002). "GABA and glutamate in the human being brain". The Neuroscientist. 8 (6): 562–573. doi:ten.1177/1073858402238515. PMID 12467378. S2CID 84891972.

- ^ Rodnina MV, Beringer 1000, Wintermeyer W (January 2007). "How ribosomes brand peptide bonds". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 32 (ane): 20–26. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2006.eleven.007. PMID 17157507.

- ^ Driscoll DM, Copeland PR (2003). "Mechanism and regulation of selenoprotein synthesis". Annual Review of Nutrition. 23 (1): 17–40. doi:10.1146/annurev.nutr.23.011702.073318. PMID 12524431.

- ^ Krzycki JA (December 2005). "The direct genetic encoding of pyrrolysine". Current Opinion in Microbiology. 8 (vi): 706–712. doi:ten.1016/j.mib.2005.10.009. PMID 16256420.

- ^ Théobald-Dietrich A, Giegé R, Rudinger-Thirion J (2005). "Evidence for the existence in mRNAs of a hairpin element responsible for ribosome dependent pyrrolysine insertion into proteins". Biochimie. 87 (9–10): 813–817. doi:x.1016/j.biochi.2005.03.006. PMID 16164991.

- ^ Wong, J. T.-F. (1975). "A Co-Evolution Theory of the Genetic Code". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 72 (5): 1909–1912. Bibcode:1975PNAS...72.1909T. doi:10.1073/pnas.72.5.1909. PMC432657. PMID 1057181.

- ^ Trifonov EN (Dec 2000). "Consensus temporal gild of amino acids and evolution of the triplet lawmaking". Cistron. 261 (1): 139–151. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(00)00476-five. PMID 11164045.

- ^ Higgs PG, Pudritz RE (June 2009). "A thermodynamic basis for prebiotic amino acid synthesis and the nature of the first genetic code". Astrobiology. 9 (5): 483–90. arXiv:0904.0402. Bibcode:2009AsBio...9..483H. doi:10.1089/ast.2008.0280. PMID 19566427. S2CID 9039622.

- ^ Kryukov GV, Castellano S, Novoselov SV, Lobanov AV, Zehtab O, Guigó R, Gladyshev VN (May 2003). "Characterization of mammalian selenoproteomes". Science. 300 (5624): 1439–1443. Bibcode:2003Sci...300.1439K. doi:10.1126/scientific discipline.1083516. PMID 12775843. S2CID 10363908. Archived from the original on 23 July 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- ^ Gromer S, Urig Due south, Becker Thousand (January 2004). "The thioredoxin system—from science to clinic". Medicinal Research Reviews. 24 (1): 40–89. doi:x.1002/med.10051. PMID 14595672. S2CID 1944741.

- ^ Tjong H (2008). Modeling Electrostatic Contributions to Poly peptide Folding and Binding (PhD thesis). Florida Land University. p. i footnote. Archived from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ Stewart L, Burgin AB (2005). Atta-Ur-Rahman, Springer BA, Caldwell GW (eds.). "Whole Gene Synthesis: A Factor-O-Matic Future". Frontiers in Drug Design and Discovery. Bentham Science Publishers. 1: 299. doi:10.2174/1574088054583318. ISBN978-ane-60805-199-1. ISSN 1574-0889. Archived from the original on 14 Apr 2021. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ Elzanowski A, Ostell J (7 Apr 2008). "The Genetic Codes". National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ^ a b Xie J, Schultz PG (December 2005). "Adding amino acids to the genetic repertoire". Current Opinion in Chemical Biological science. 9 (vi): 548–554. doi:x.1016/j.cbpa.2005.x.011. PMID 16260173.

- ^ a b Wang Q, Parrish AR, Wang L (March 2009). "Expanding the genetic code for biological studies". Chemistry & Biology. 16 (3): 323–336. doi:ten.1016/j.chembiol.2009.03.001. PMC2696486. PMID 19318213.

- ^ Simon K (2005). Emergent ciphering: emphasizing bioinformatics . New York: AIP Press/Springer Science+Business organization Media. pp. 105–106. ISBN978-0-387-22046-8.

- ^ Vermeer C (March 1990). "Gamma-carboxyglutamate-containing proteins and the vitamin K-dependent carboxylase". The Biochemical Journal. 266 (3): 625–636. doi:ten.1042/bj2660625. PMC1131186. PMID 2183788.

- ^ Bhattacharjee A, Bansal Grand (March 2005). "Collagen structure: the Madras triple helix and the current scenario". IUBMB Life. 57 (iii): 161–172. doi:10.1080/15216540500090710. PMID 16036578. S2CID 7211864.

- ^ Park MH (February 2006). "The post-translational synthesis of a polyamine-derived amino acid, hypusine, in the eukaryotic translation initiation gene 5A (eIF5A)". Journal of Biochemistry. 139 (ii): 161–169. doi:10.1093/jb/mvj034. PMC2494880. PMID 16452303.

- ^ Blenis J, Resh Medico (Dec 1993). "Subcellular localization specified by protein acylation and phosphorylation". Current Opinion in Cell Biology. five (6): 984–989. doi:10.1016/0955-0674(93)90081-Z. PMID 8129952.

- ^ Curis E, Nicolis I, Moinard C, Osowska S, Zerrouk N, Bénazeth S, Cynober L (November 2005). "Almost all nearly citrulline in mammals". Amino Acids. 29 (3): 177–205. doi:10.1007/s00726-005-0235-4. PMID 16082501. S2CID 23877884.

- ^ Coxon KM, Chakauya E, Ottenhof HH, Whitney HM, Blundell TL, Abell C, Smith AG (August 2005). "Pantothenate biosynthesis in higher plants". Biochemical Society Transactions. 33 (Pt 4): 743–746. doi:10.1042/BST0330743. PMID 16042590.

- ^ Sakami W, Harrington H (1963). "Amino acrid metabolism". Almanac Review of Biochemistry. 32 (1): 355–398. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.32.070163.002035. PMID 14144484.

- ^ Brosnan JT (Apr 2000). "Glutamate, at the interface between amino acid and carbohydrate metabolism". The Journal of Nutrition. 130 (4S Suppl): 988S–990S. doi:10.1093/jn/130.4.988S. PMID 10736367.

- ^ Young VR, Ajami AM (September 2001). "Glutamine: the emperor or his clothes?". The Periodical of Nutrition. 131 (9 Suppl): 2449S–2459S, 2486S–2487S. doi:10.1093/jn/131.9.2449S. PMID 11533293.

- ^ Young VR (August 1994). "Adult amino acrid requirements: the instance for a major revision in current recommendations". The Journal of Nutrition. 124 (eight Suppl): 1517S–1523S. doi:10.1093/jn/124.suppl_8.1517S. PMID 8064412.

- ^ Fürst P, Stehle P (June 2004). "What are the essential elements needed for the determination of amino acid requirements in humans?". The Periodical of Nutrition. 134 (6 Suppl): 1558S–1565S. doi:x.1093/jn/134.half-dozen.1558S. PMID 15173430.

- ^ Reeds PJ (July 2000). "Disposable and indispensable amino acids for humans". The Periodical of Diet. 130 (7): 1835S–1840S. doi:ten.1093/jn/130.7.1835S. PMID 10867060.

- ^ Imura K, Okada A (Jan 1998). "Amino acrid metabolism in pediatric patients". Diet. 14 (1): 143–148. doi:ten.1016/S0899-9007(97)00230-Ten. PMID 9437700.

- ^ Lourenço R, Camilo ME (2002). "Taurine: a conditionally essential amino acid in humans? An overview in wellness and illness". Nutricion Hospitalaria. 17 (6): 262–270. PMID 12514918.

- ^ Holtcamp W (March 2012). "The emerging science of BMAA: do blue-green alga contribute to neurodegenerative disease?". Ecology Health Perspectives. 120 (3): A110–A116. doi:10.1289/ehp.120-a110. PMC3295368. PMID 22382274.

- ^ Cox PA, Davis DA, Mash DC, Metcalf JS, Banack SA (Jan 2016). "Dietary exposure to an environmental toxin triggers neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid deposits in the brain". Proceedings: Biological Sciences. 283 (1823): 20152397. doi:10.1098/rspb.2015.2397. PMC4795023. PMID 26791617.

- ^ a b Brook MS, Wilkinson DJ, Phillips Be, Perez-Schindler J, Philp A, Smith K, Atherton PJ (Jan 2016). "Skeletal muscle homeostasis and plasticity in youth and ageing: affect of nutrition and practise". Acta Physiologica. 216 (1): xv–41. doi:10.1111/apha.12532. PMC4843955. PMID 26010896.

- ^ Lipton JO, Sahin M (October 2014). "The neurology of mTOR". Neuron. 84 (2): 275–291. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2014.09.034. PMC4223653. PMID 25374355.

Figure 2: The mTOR Signaling Pathway Archived 1 July 2020 at the Wayback Auto - ^ a b Phillips SM (May 2014). "A brief review of critical processes in do-induced muscular hypertrophy". Sports Medicine. 44 (Suppl. i): S71–S77. doi:10.1007/s40279-014-0152-3. PMC4008813. PMID 24791918.

- ^ Broadley KJ (March 2010). "The vascular effects of trace amines and amphetamines". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 125 (iii): 363–375. doi:x.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.11.005. PMID 19948186.

- ^ Lindemann Fifty, Hoener MC (May 2005). "A renaissance in trace amines inspired by a novel GPCR family unit". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 26 (5): 274–281. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2005.03.007. PMID 15860375.

- ^ Wang X, Li J, Dong Grand, Yue J (February 2014). "The endogenous substrates of brain CYP2D". European Journal of Pharmacology. 724: 211–218. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.12.025. PMID 24374199.

- ^ Savelieva KV, Zhao Southward, Pogorelov VM, Rajan I, Yang Q, Cullinan Eastward, Lanthorn TH (2008). Bartolomucci A (ed.). "Genetic disruption of both tryptophan hydroxylase genes dramatically reduces serotonin and affects beliefs in models sensitive to antidepressants". PLOS ONE. 3 (10): e3301. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.3301S. doi:10.1371/periodical.pone.0003301. PMC2565062. PMID 18923670.

- ^ Shemin D, Rittenberg D (December 1946). "The biological utilization of glycine for the synthesis of the protoporphyrin of hemoglobin". The Periodical of Biological Chemistry. 166 (ii): 621–625. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)35200-6. PMID 20276176. Archived from the original on seven May 2022. Retrieved three November 2008.

- ^ Tejero J, Biswas A, Wang ZQ, Folio RC, Haque MM, Hemann C, Zweier JL, Misra S, Stuehr DJ (November 2008). "Stabilization and label of a heme-oxy reaction intermediate in inducible nitric-oxide synthase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 283 (48): 33498–33507. doi:10.1074/jbc.M806122200. PMC2586280. PMID 18815130.

- ^ Rodríguez-Caso C, Montañez R, Cascante Grand, Sánchez-Jiménez F, Medina MA (August 2006). "Mathematical modeling of polyamine metabolism in mammals". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 281 (31): 21799–21812. doi:10.1074/jbc.M602756200. PMID 16709566.

- ^ a b Stryer 50, Berg JM, Tymoczko JL (2002). Biochemistry (5th ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman. pp. 693–698. ISBN978-0-7167-4684-3.

- ^ Hylin JW (1969). "Toxic peptides and amino acids in foods and feeds". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 17 (iii): 492–496. doi:ten.1021/jf60163a003.

- ^ Turner BL, Harborne JB (1967). "Distribution of canavanine in the institute kingdom". Phytochemistry. 6 (vi): 863–866. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(00)86033-1.

- ^ Ekanayake S, Skog M, Asp NG (May 2007). "Canavanine content in sword beans (Canavalia gladiata): assay and effect of processing". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 45 (5): 797–803. doi:ten.1016/j.fct.2006.10.030. PMID 17187914.

- ^ Rosenthal GA (2001). "L-Canavanine: a college plant insecticidal allelochemical". Amino Acids. 21 (three): 319–330. doi:10.1007/s007260170017. PMID 11764412. S2CID 3144019.

- ^ Hammond, Andrew C. (1 May 1995). "Leucaena toxicosis and its control in ruminants". Journal of Animal Science. 73 (5): 1487–1492. doi:ten.2527/1995.7351487x. PMID 7665380. Archived from the original on 7 May 2022. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ a b Leuchtenberger W, Huthmacher K, Drauz K (November 2005). "Biotechnological production of amino acids and derivatives: electric current status and prospects". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 69 (1): ane–8. doi:10.1007/s00253-005-0155-y. PMID 16195792. S2CID 24161808.

- ^ Ashmead HD (1993). The Role of Amino Acid Chelates in Animal Nutrition. Westwood: Noyes Publications.

- ^ Garattini Due south (April 2000). "Glutamic acid, twenty years later". The Journal of Nutrition. 130 (4S Suppl): 901S–909S. doi:10.1093/jn/130.4.901S. PMID 10736350.

- ^ Stegink LD (July 1987). "The aspartame story: a model for the clinical testing of a food condiment". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 46 (1 Suppl): 204–215. doi:10.1093/ajcn/46.ane.204. PMID 3300262.

- ^ Albion Laboratories, Inc. "Albion Ferrochel Website". Archived from the original on 3 September 2011. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ^ Ashmead HD (1986). Foliar Feeding of Plants with Amino Acrid Chelates. Park Ridge: Noyes Publications.

- ^ Turner EH, Loftis JM, Blackwell AD (March 2006). "Serotonin a la carte: supplementation with the serotonin precursor 5-hydroxytryptophan". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 109 (iii): 325–338. doi:x.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.06.004. PMID 16023217. Archived from the original on 13 Apr 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- ^ Kostrzewa RM, Nowak P, Kostrzewa JP, Kostrzewa RA, Brus R (March 2005). "Peculiarities of 50-DOPA treatment of Parkinson'south disease". Amino Acids. 28 (2): 157–164. doi:10.1007/s00726-005-0162-four. PMID 15750845. S2CID 33603501.

- ^

- ^ Cruz-Vera LR, Magos-Castro MA, Zamora-Romo E, Guarneros G (2004). "Ribosome stalling and peptidyl-tRNA drop-off during translational delay at AGA codons". Nucleic Acids Inquiry. 32 (15): 4462–4468. doi:x.1093/nar/gkh784. PMC516057. PMID 15317870.

- ^ Andy C (October 2012). "Molecules 'as well unsafe for nature' impale cancer cells". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 25 April 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ^ "Lethal DNA tags could keep innocent people out of jail". New Scientist. 2 May 2013. Archived from the original on thirty April 2015. Retrieved 24 Baronial 2017.

- ^ Hanessian S (1993). "Reflections on the total synthesis of natural products: Art, craft, logic, and the chiron approach". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 65 (half dozen): 1189–1204. doi:x.1351/pac199365061189. S2CID 43992655.

- ^ Blaser HU (1992). "The chiral pool equally a source of enantioselective catalysts and auxiliaries". Chemical Reviews. 92 (5): 935–952. doi:10.1021/cr00013a009.

- ^ Sanda F, Endo T (1999). "Syntheses and functions of polymers based on amino acids". Macromolecular Chemical science and Physics. 200 (12): 2651–2661. doi:x.1002/(SICI)1521-3935(19991201)200:12<2651::Assistance-MACP2651>three.0.CO;two-P.

- ^ Gross RA, Kalra B (Baronial 2002). "Biodegradable polymers for the environment". Science. 297 (5582): 803–807. Bibcode:2002Sci...297..803G. doi:10.1126/science.297.5582.803. PMID 12161646. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- ^ Low KC, Wheeler AP, Koskan LP (1996). Commercial poly(aspartic acid) and Its Uses. Advances in Chemistry Serial. Vol. 248. Washington, D.C.: American Chemical Gild.

- ^ Thombre SM, Sarwade BD (2005). "Synthesis and Biodegradability of Polyaspartic Acid: A Disquisitional Review". Periodical of Macromolecular Science, Part A. 42 (nine): 1299–1315. doi:10.1080/10601320500189604. S2CID 94818855.

- ^ Bourke SL, Kohn J (Apr 2003). "Polymers derived from the amino acid L-tyrosine: polycarbonates, polyarylates and copolymers with poly(ethylene glycol)". Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 55 (4): 447–466. doi:10.1016/S0169-409X(03)00038-3. PMID 12706045.

- ^ Drauz K, Grayson I, Kleemann A, Krimmer H, Leuchtenberger W, Weckbecker C (2006). Ullmann'south Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:ten.1002/14356007.a02_057.pub2.

- ^ Jones RC, Buchanan BB, Gruissem W (2000). Biochemistry & molecular biology of plants. Rockville, Md: American Guild of Plant Physiologists. pp. 371–372. ISBN978-0-943088-39-6.

- ^ Brosnan JT, Brosnan ME (June 2006). "The sulfur-containing amino acids: an overview". The Journal of Nutrition. 136 (6 Suppl): 1636S–1640S. doi:10.1093/jn/136.6.1636S. PMID 16702333.

- ^ Kivirikko KI, Pihlajaniemi T (1998). "Collagen hydroxylases and the protein disulfide isomerase subunit of prolyl 4-hydroxylases". Advances in Enzymology and Related Areas of Molecular Biological science. Advances in Enzymology – and Related Areas of Molecular Biology. Vol. 72. pp. 325–398. doi:10.1002/9780470123188.ch9. ISBN9780470123188. PMID 9559057.

- ^ Whitmore L, Wallace BA (May 2004). "Analysis of peptaibol sequence composition: implications for in vivo synthesis and aqueduct formation". European Biophysics Journal. 33 (3): 233–237. doi:10.1007/s00249-003-0348-one. PMID 14534753. S2CID 24638475.

- ^ Alexander L, Grierson D (October 2002). "Ethylene biosynthesis and activity in tomato: a model for climacteric fruit ripening". Periodical of Experimental Botany. 53 (377): 2039–2055. doi:10.1093/jxb/erf072. PMID 12324528.

- ^ Elmore DT, Barrett GC (1998). Amino acids and peptides . Cambridge, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland: Cambridge Academy Press. pp. 48–60. ISBN978-0-521-46827-five.

- ^ Gutteridge A, Thornton JM (November 2005). "Agreement nature'southward catalytic toolkit". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. xxx (11): 622–629. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2005.09.006. PMID 16214343.

- ^ Ibba M, Söll D (May 2001). "The renaissance of aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis". EMBO Reports. two (5): 382–387. doi:10.1093/embo-reports/kve095. PMC1083889. PMID 11375928.

- ^ Lengyel P, Söll D (June 1969). "Machinery of poly peptide biosynthesis". Bacteriological Reviews. 33 (ii): 264–301. doi:x.1128/MMBR.33.2.264-301.1969. PMC378322. PMID 4896351.

- ^ Wu G, Fang YZ, Yang S, Lupton JR, Turner ND (March 2004). "Glutathione metabolism and its implications for health". The Periodical of Nutrition. 134 (3): 489–492. doi:10.1093/jn/134.3.489. PMID 14988435.

- ^ Meister A (November 1988). "Glutathione metabolism and its selective modification". The Journal of Biological Chemical science. 263 (33): 17205–17208. doi:x.1016/S0021-9258(xix)77815-half-dozen. PMID 3053703.

- ^ Carpino LA (1992). "ane-Hydroxy-7-azabenzotriazole. An efficient peptide coupling additive". Journal of the American Chemical Gild. 115 (ten): 4397–4398. doi:10.1021/ja00063a082.

- ^ Marasco D, Perretta G, Sabatella M, Ruvo M (October 2008). "Past and hereafter perspectives of synthetic peptide libraries". Electric current Protein & Peptide Science. 9 (5): 447–467. doi:x.2174/138920308785915209. PMID 18855697.

- ^ Konara Southward, Gagnona Thousand, Clearfield A, Thompson C, Hartle J, Ericson C, Nelson C (2010). "Structural determination and label of copper and zinc bis-glycinates with X-ray crystallography and mass spectrometry". Periodical of Coordination Chemistry. 63 (19): 3335–3347. doi:10.1080/00958972.2010.514336. S2CID 94822047.

- ^ Stipanuk MH (2006). Biochemical, physiological, & molecular aspects of human being nutrition (second ed.). Saunders Elsevier.

- ^ Dghaym RD, Dhawan R, Arndtsen BA (September 2001). "The Utilize of Carbon Monoxide and Imines as Peptide Derivative Synthons: A Facile Palladium-Catalyzed Synthesis of α-Amino Acid Derived Imidazolines". Angewandte Chemie. 40 (17): 3228–3230. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980703)37:12<1634::Help-ANIE1634>iii.0.CO;ii-C. PMID 29712039.

- ^ Muñoz-Huerta RF, Guevara-Gonzalez RG, Contreras-Medina LM, Torres-Pacheco I, Prado-Olivarez J, Ocampo-Velazquez RV (August 2013). "A review of methods for sensing the nitrogen status in plants: advantages, disadvantages and recent advances". Sensors. Basel, Switzerland. 13 (8): 10823–43. Bibcode:2013Senso..1310823M. doi:x.3390/s130810823. PMC3812630. PMID 23959242.

- ^ Martin PD, Malley DF, Manning Grand, Fuller L (2002). "Determination of soil organic carbon and nitrogen at thefield level using near-infrared spectroscopy". Canadian Journal of Soil Scientific discipline. 82 (four): 413–422. doi:10.4141/S01-054.

Farther reading [edit]

- Tymoczko JL (2012). "Protein Composition and Structure". Biochemistry . New York: Due west. H. Freeman and company. pp. 28–31. ISBN9781429229364.

- Doolittle RF (1989). "Redundancies in protein sequences". In Fasman GD (ed.). Predictions of Protein Construction and the Principles of Protein Conformation. New York: Plenum Press. pp. 599–623. ISBN978-0-306-43131-ix. LCCN 89008555.

- Nelson DL, Cox MM (2000). Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry (3rd ed.). Worth Publishers. ISBN978-1-57259-153-0. LCCN 99049137.

- Meierhenrich U (2008). Amino acids and the asymmetry of life (PDF). Berlin: Springer Verlag. ISBN978-3-540-76885-ii. LCCN 2008930865. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012.

{{cite volume}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

External links [edit]

-

Media related to Amino acid at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Amino acid at Wikimedia Commons

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amino_acid

Posted by: jacobsbeasto.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Is The Advantage In Animals Coupling Nitrogenous Waste"

Post a Comment